StarX Garden

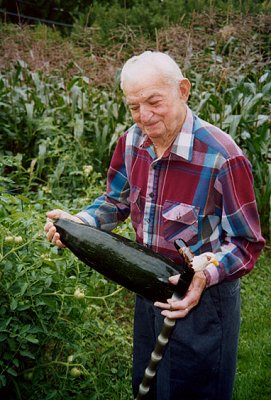

Gardening is my favorite hobby. I love any kind of plant or flower, but I especially like growing vegetables. My kids say I can make anything grow!

I live with one of my daughters and her family now. I moved in right after my heart surgery. Before that, I owned a condo and would walk to my daughters to work in my garden. When I moved back to Michigan from Daytona Beach, Florida, she and her husband let me have my own spot in the side yard to plant my first garden in 15 years! I really missed that! I enjoy it so much! Now all I do is go out the door and I'm there, looking at all of my beautiful plants.

Below you will find some gardening tips. Later we will be adding pictures of my currant garden & some items from the past, including newspaper articles on some of my wonderful garden plants.

**************************************************

Dad's pages will continue to be added to.

In Loving Memory.

(3/19/1917 - 2/26/2007)

**************************************************

LADYBUGS

Attract Ladybugs... They're good for your garden

Attract Ladybugs... They're good for your garden

Luring Ladybugs Into Your

Garden:

Of all

the insects in the garden, the ladybug is probably the most

easily recognized. Ladybugs, (also called lady beetles or

ladybirds,) are a gardener's best friend. Not only do they

feed on insect pests, especially aphids, but their bright coloring

also brings cheer into the garden.

Attracting

them into your garden takes some planning but can help immensely with

your pest control. However, if you just don't have the space to

plant the types of plants that ladybugs like, releasing commercially

bought ladybugs can help you clean up infested plants while you work

to establish your own population.

Identification:

Adult lady beetles are usually oval or domed shaped, and

can range in color from red to orange. The number of black

markings can also range anywhere from no spots to 15 spots.

Some species are even solid black or black with a red spot (the

Twice Stabbed Lady Beetle).

The young, larval form of the ladybug

is often less recognized. They tend to resemble tiny, six

legged alligators, blue-black in colour with orange spots.

Often, gardeners unknowingly squish or spray the larval form of the

ladybug, not knowing what a benefit they are to the garden.

Both adults and larvae feed on many

different soft-bodied insects but aphids are their main food

source. One larva will eat about 400 aphids during its

development and a single adult can eat a whopping 5,000 aphids in

its lifetime. They will also eat other insects such as

mealybugs and spider mites as well as the eggs of the Colorado Potato

Beetle and European Corn Borer.

Life Cycle: Within a

year, there can be as many as 5 to 6 generations of ladybugs as the

average time for growth from egg to adult only takes about 3 to 4

weeks. In the spring, adults find food and then the females lay

anywhere from 50 to 300 eggs. The tiny eggs are yellow & oval

shaped and are usually found in clusters of 10 to 50, near aphid

colonies. The eggs take 3 to 5 days to hatch and the larvae

voraciously feed on aphids for 2 to 3 weeks before they grow into

adults.

In the fall, adults hibernate in plant

refuse and crevices. They often do this in groups where several

hundred adults will gather at the base of a tree, along a fencerow or

under a rock. They especially like areas where leaves protect

them from cold winter temperatures.

Attracting Ladybugs in the

Garden: Apart from aphids, ladybugs also require a source of

pollen for food and are attracted to specific types of plants.

The most popular ones have umbrella shaped flowers such as fennel,

dill, caraway, angelica, tansy, wild carrot & yarrow. Other

plants that also attract ladybugs include cosmos (especially the

white ones), coreopsis, and scented geraniums, and dandelions.

Apart from planting attractive plants

in the garden, you can also promote ladybug populations by cutting

back on spraying insecticides. Not only are ladybugs sensitive

to most synthetic insecticides, but if the majority of their food

source is gone, they won't lay their eggs in your garden. As

difficult as it may be, allowing aphids to live on certain plants is

necessary to ensure that there is enough food for ladybugs. In

addition, resist the urge to squish bugs & eggs in the garden, unless

you're certain that they are not beneficial.

Purchasing Ladybugs:

Sometimes, there just isn't enough room in the garden to

have ladybug-attracting plants. Purchasing ladybugs can help

a population become established.

Scientists have found that

indoor-reared ladybugs fail to find their own food when released

outside so the majority of commercially available ladybugs are

collected from the wild. Before releasing them into the garden,

here are a few tips to help ensure that they stay where you want

them:

1. Only release ladybugs after sun down or

before sun-up. Ladybugs navigate by the sun and in the evenings

& early mornings, they tend to stay put.

2. Pre-water the area where you are releasing

them. Not only will the ladybugs appreciate the drink,

moisture on the leaves helps the ladybugs to "stick" to plants.

3. In the warm months, it helps to chill the

ladybugs in the fridge before releasing them. Ladybugs tend to

crawl more than fly in colder temperatures and the overnight stay in

the fridge won't harm them in any way.

4. On severely infested plants like roses,

drape a floating row cover or thin sheet over the plant and release

the ladybugs underneath. Within a day, the ladybugs will have

found the aphids and will be happily munching away at them.

The Asian Ladybug:

If you are planning to buy ladybugs for your garden or

greenhouse, I encourage you to select the native ladybugs species,

Hippodamia convergens, rather than the Asian ladybug, Harmonia

axyridis. Although the Asian is very effective at controlling

aphids and is often the species of choice for commercial greenhouse

growers, it is the main cause for "ladybug infestations" inside

houses.

While the native ladybug is happy to

hibernate outdoors, the Asian species requires warmer temperatures

and often ends up becoming a pest to homeowners as it congregates in

large numbers inside. It also seems to be establishing fairly

large numbers in the wild and there is some concern it will begin

competing with the native species. Some suppliers of predatory

insects do sell both species but it's best to choose the native one

if you can.

**************************************************

ASPARAGUS

This

vegetable has attractive, feathery fern-like foliage that can grow up

to 3 feet tall. Time is required to prepare the asparagus bed,

but if done right the bed will last for years.

This

vegetable has attractive, feathery fern-like foliage that can grow up

to 3 feet tall. Time is required to prepare the asparagus bed,

but if done right the bed will last for years.

Planting: In the north,

plants should be set out in early spring. In the South, set

them out in the fall because it can be so hot in the summer that

the young plants may not survive. Asparagus does well in most

types of soil, but it should be well drained. Place plants 2

feet apart with 5 feet between rows. Once the bed is

established, which takes three seasons, 25-30 crowns will produce

enough asparagus for most families.

Dig a trench 12-18 inches deep and the

length of your row. Add 6-7 inches of aged manure or compost

or a little peat moss. Sprinkle on a dusting of balanced

fertilizer and add a couple of inches of soil from your garden.

Mix well.

With the mixture you have made, build up

mounds at the bottom of the trench about a foot apart. Set

each crown on top of a mound and drape the roots down the sides.

Growth will be slow if roots are placed flat.

Fill the trenches making sure the crowns

are at least four inches beneath the soil surface. The soil

level of the row should be a little below the rest of the garden.

When the shoots grow up, fill in the trench with a little more soil

to give the stalks good support.

First Year Care:

Place a thick mulch around the small spears after they come up to

keep the weeds down and to hold in moisture. Let the new plants

grow through the summer and fall without cutting shoots or ferns.

Let the tops die down in the late fall without interference.

Choosing Plants:

Begin with two-year-old roots. One-year-old plants will be

cheaper but these younger plants often don't survive transplanting,

and your first harvest will be delayed for a year. The very

patient gardener may want to try starting seeds in special beds and

transplant them to their permanent spot in the garden when they are

two years old.

To Store Asparagus:

Stand the spears upright in a jar with about an inch of water in the

bottom. Keep the jar in the refrigerator.

Second Year Care:

This spring and every spring you need to cut the old ferns that died

over the previous fall and winter and clear them out before the

plants begin to grow. Also remove any mulch that's left in

the bed. Fertilize and cultivate well between the rows.

Be careful of spreading roots. Mulch around the spears when

they are tall enough. Don't harvest this year.

Third Year Care: Repeat

the process of cutting back the ferns, removing the mulch and

fertilizing. Harvest some spears by cutting with a sharp knife

just below the soil when they are 6-8 inches tall. Cut only the

ones that are as thick as your finger and let the skinny ones grow

into ferns.

Each year

you will need to leave some spears to grow into ferns. After the last

harvest, pull all weeds and fertilize the bed. Mulch

heavily to prevent the growth of weeds.

**************************************************

BEANS

Types of Beans:

Beans are usually divided into three types.

Types of Beans:

Beans are usually divided into three types.

Green and Yellow Snap Beans:

These used to be called string beans, but the string has

been bred out of most varieties. They come in bush and pole

varieties. Pole beans will require some kind of support, and

will produce the heaviest yield.

Shell Beans: These

include lima beans, southern peas, and horticultural beans.

Dry Beans: Dry beans

come from plants that have completed their growth and produced hard,

dry seeds inside their pods. When mature, the beans are packed

with protein.

Planting time: Plant

mid-spring to late-summer. Be sure danger of frost has

passed.

Soil: Well

drained. Root system is shallow.

Sowing seeds: Sow

seeds directly into beds. Climbing beans should be 6 inches

apart in rows 3 feet apart. Dwarf varieties should be spaced

2 inches apart.

Fertilizer: Add lime if

the soil is acidic. Rich soil or soil to which compost has been

added will be fine until the beans begin to flower. At this

time, side dress with manure or additional compost.

Sun: Plant in full

sun.

Temperature: Beans

can't tolerate frost. They need warm soil.

Support: Climbing

varieties require trellises, poles, or other means of support at

least 8 feet tall.

Watering: You must

water in most areas because of the shallow root system. At a

minimum, beans should be watered after sowing, and when seedlings

appear and during flowering.

Maintenance: Hill

rows with soil during early growth to protect the plants from the

wind. Be careful when weeding the seedlings because the roots

are near the surface.

Harvesting: Dwarf

beans will mature in about 10 weeks and climbing beans will be ready

in 10-12 weeks. Frequent picking will result in

increased flowering and greater yields. Be careful when pulling

the pods off so you don't damage the vines. The pods are ready

to pick when they snap easily and seeds are not yet fully

developed. Avoid harvesting in very hot or very cold

weather.

Bean Diseases: Here

are a few tips tp help avoid disease.

1.

Stay out of the garden when plants are wet.

2.

Rotate the bean crop each year to avoid soil-borne diseases.

3.

Use mulch for walkways to keep rain from splashing soil and disease

spores on the plants.

4.

Never leave dead plant material in the garden, as this encourages

disease.

**************************************************

BEETS

Beets

thrive in cool weather, and can be planted in spring and late

summer. Roots may become woody in very hot weather. They

can tolerate a light frost, but not scorching heat. Sow seeds

2 inches apart in square foot blocks about 1/2 inch deep. They

will germinate in about two weeks. Thin to 3 or 4 inches apart,

then mulch with clean straw. Beets can tolerate partial shade,

however full sun is preferred.

Beets

thrive in cool weather, and can be planted in spring and late

summer. Roots may become woody in very hot weather. They

can tolerate a light frost, but not scorching heat. Sow seeds

2 inches apart in square foot blocks about 1/2 inch deep. They

will germinate in about two weeks. Thin to 3 or 4 inches apart,

then mulch with clean straw. Beets can tolerate partial shade,

however full sun is preferred.

Preparing the Soil:

Till soil 6 to 8 inches deep. Work in plenty of fertilizer to

improve the soil. It is difficult if not impossible to grow

good beets in clay soil without a raised bed. Rake soil well

to remove stones and debris.

Beets need

an alkaline soil, and the addition of a pound of lime for each square

yard of bed will sweeten the soil.

Planting: Sow beets

all season long in subtropical climates; during spring and autumn in

warm regions, and spring through early autumn in colder areas.

Maintenance: Good

beets depend on a steady moisture supply. A light mulch around

young beets will help the soil retain the necessary moisture.

They do not tolerate weeds, but be careful not to damage the roots

when weeding.

Beets are

sensitive to boron deficiency, which causes blackspot, sickly growth,

and poor taste. Only small amounts are needed, and if you use

compost, the soil will be adequate. If you're in doubt,

sprinkle a little borax around the plant.

Beets are

seldom bothered by insects or disease.

Harvesting: Beets

mature in approximately 3-4 months, however tender young "baby

beets" are a real treat. They lose flavor and the centers become

woody as they get bigger.

**************************************************

BERRIES

Berries

are almost the perfect home garden plant. They are easy to

grow, requiring little more than a patch of full sun and some

well-drained soil. Most have perennial roots with shoots that

are biennial. This means that the shoots (called "canes") grow

vegetatively in the first growing season, go through a dormant

season, then leaf out, flower, fruit, and die during the second

growing season.

Berries

are almost the perfect home garden plant. They are easy to

grow, requiring little more than a patch of full sun and some

well-drained soil. Most have perennial roots with shoots that

are biennial. This means that the shoots (called "canes") grow

vegetatively in the first growing season, go through a dormant

season, then leaf out, flower, fruit, and die during the second

growing season.

Raspberries

and blackberries are the two most common bramble crops. Red,

black, and purple raspberries are the three most commonly grown

raspberry types. Red raspberries have erect canes and are

propagated by suckers. Black raspberries have arched canes that

root at the tips. Purple raspberries are hybrids of red and

black varieties.

Planting: Unless

otherwise stated, these are the basic planting instructions

for berry bushes: Dig a hole twice the size of the root

ball and a proper depth that is level or slightly lower than the soil

surface. Add organic matter (peat moss or humus) to the soil

and mix thoroughly. The amount of organic matter should equal

1/2 the volume of the soil. Place the plant into the hole

making sure that the hole has the proper width and depth. Begin

to back fill the hole halfway. Make sure that the plant is

straight before too much soil is in the hole. Tamp the soil

around the root ball. Repeat the procedure of filling and

tamping until the hole has been filled. Give the plant a good

initial watering, then again every 3-5 days after planting. Top

dress with shredded bark (2" deep) and fertilizer (1/2 lb. per year

since planting, starting with the second season).

Raspberries

grow best in cool climates, and can tolerate a wide range of soil

types from sandy loam to clay. The most important requirement

for the berries is that the soil is deep so that the roots are not

restricted. Raspberries should not be planted in an area

following the cultivation of tomatoes, eggplant or

potatoes. Diseases that affect these plants may remain in the

soil and damage the berries. Plants can be grown in hills or in

rows. Red raspberry plants should be set 2 to 3 feet apart if

planted in rows. Before planting, cut the tops of the plants

back to six inches. Set the plants into the hole so they are 2

to 3 inches deeper than they were in the nursery. Water after

transplanting.

To get

maximum yields from raspberries, apply fertilizer every year in the

early spring just as new growth begins. Manure works well as

does a commercial 5-10-5 fertilizer. Apply this as a top

dressing at the rate of 8 ounces per plant, or spread in a wide band

no closer than about 6 inches from the crown around each hill.

Some red

raspberry varieties have long, slender canes that must be

tied. They can be staked or tied to a trellis. Set the

trellis posts at either end of your raspberry row and run wires

between them. Most red raspberry varieties are stout caned and

can be planted in hills without training them to stakes. The

wires will just support the boughs when laden with fruit.

Raspberry

canes are biennial; they grow the first year, fruit the second,

then die. Only the crown and the roots are perennial. Old

canes should be removed as soon as the fruit is harvested. New

canes grow from buds on the base of the old canes. Two new

shoots usually come up each year. In addition, suckers grow

directly from the roots of red raspberries. The new canes and

suckers should be thinned immediately after harvest.

Berries

should be picked in the morning after the dew has

evaporated. If picked in the afternoon, the berries will take

longer to cool down, which shortens their shelf life.

Blackberries and raspberries should be picked when they are

plump, sweet, fully colored and can be easily pulled off the

stem. Different varieties may produce berries at different

times, providing a longer harvesting period.

Summer

fruiting cultivars should have the old canes cut out as soon as the

fruit has been picked. Autumn fruiting cultivars should be cut

down to within a few inches of the ground in late February.

**************************************************

BROCCOLI

A head of

broccoli is a cluster of flower buds. When the head is young

its individual buds are packed very tightly. As long as the

buds stay tight, just let the head grow. Once the head begins

to loosen and spread out, they are about to bloom and the head should

be cut immediately, regardless of the size.

A head of

broccoli is a cluster of flower buds. When the head is young

its individual buds are packed very tightly. As long as the

buds stay tight, just let the head grow. Once the head begins

to loosen and spread out, they are about to bloom and the head should

be cut immediately, regardless of the size.

Once the

main head has been cut, many smaller heads, called side shoots, will

form on other parts of the plants. They may not be large, but

the number of shoots often makes up for the decreased size and they

are just as good.

Broccoli

can be grown anywhere except in the hottest and coldest climates,

but it does require cool weather to reach maturity. Ideal

temperatures are not more than 77 degrees during the day and not

less than 60 degrees at night.

Location: Plant in

a well drained, sunny location. Broccoli can be planted in

containers outdoors.

Cultivation:

Prepare the soil with manures and compost and provide extra nitrogen

supplement if the soil is sandy.

Planting: Sow seeds

1/2 inch deep into the soil. After thinning, plants should be

about 10 inches apart. Successive sowings should occur at one

month intervals. If you are starting seeds indoors, use 4 inch

peat pots and transplant when 4 leaves have appeared (6-8 weeks

after planting).

Watering: The plant

grows quickly, so keep soil moist by watering often, if

necessary. Plants requires less water as the heads begin to

mature.

Fertilizing: Manure,

especially poultry manure, is an excellent fertilizer for

broccoli. Weekly feedings with liquid seaweed fertilizer also

improves crops.

Harvesting: When

buds are large and firm but are not yet flowering, cut the large

central head leaving about 6 inches of stalk attached.

**************************************************

CABBAGE

If the heads begin to crack, that means that the inside of the head is growing faster than the outside is. This is sometimes caused by over-fertilization. If it is allowed to continue to crack, the cabbage will go to seed. To stop this, give the whole plant a 1/2 turn to break off some of the roots. If this does not stop the cracking, give it another 1/4 turn a few days later.

If the heads begin to crack, that means that the inside of the head is growing faster than the outside is. This is sometimes caused by over-fertilization. If it is allowed to continue to crack, the cabbage will go to seed. To stop this, give the whole plant a 1/2 turn to break off some of the roots. If this does not stop the cracking, give it another 1/4 turn a few days later.

Cabbage will grow in a wide range of climates. It will tolerate frost but not extreme heat that can cause the head to split.

Locate plants in a well drained, sunny location. Soil should be fertilized.

Cabbage grows quickly, so keep the soil well watered.

Planting: Sow seeds 1/4 inch deep and 3 inches apart in seed trays or flats. Transplants can be placed in the garden in the spring in cool zones and year round in other areas. Transplant seedlings when 4 inches tall with 4-5 leaves. Plant them about a foot apart. Harden off before transplanting by withholding water for a couple of days.

Watering: Keep the topsoil moist.

Fertilizing: Work in plenty of manure. Poultry manure is especially good.

Harvesting: Plants mature in 14-16 weeks. Pick when the head is firm. Remove it from the stem by cutting it. Leave the outer leaves on the stem.

**************************************************

CARROTS

Preparing the Soil:

Carrots need a well-drained, stone free soil that has been

deeply worked. If the root meets an obstacle in the early

stages of growth, it will branch or may simply stop growing.

Carrots like full sun but will tolerate partial shade, especially

if the weather is very warm.

Preparing the Soil:

Carrots need a well-drained, stone free soil that has been

deeply worked. If the root meets an obstacle in the early

stages of growth, it will branch or may simply stop growing.

Carrots like full sun but will tolerate partial shade, especially

if the weather is very warm.

Carrots produce best in a raised

bed. Till the soil to a depth of at least 8 inches, adding

plenty of compost or well-rotted manure. Potassium promotes

solid, sweet carrots. Wood ashes contain highly soluble

potassium, and reaches the plants quickly. As you prepare

the soil, work wood ashes into the top 4 inches of the soil, where

feeder roots thrive. Add lime if the soil tends to be acid.

Planting: Carrots

are cool-weather vegetables, so start sowing about two weeks before

the last expected frost in your area. Make successive plantings

every three weeks until the hottest part of the summer. Furrows

should be about 3/4 inch deep and 4 inches apart.

Place a 1/2 inch layer of peat moss in

the bottom of each furrow, sow the seeds sparingly on top, then cover

with about 1/4 inch of soil. Seeds must be kept moist to

germinate. Mulching with straw will help hold the moisture, and

will also make it easier to water without disturbing the seeds.

When sowing seeds, try to space them 1/2

inch apart. The tiny seeds make spacing difficult, but it will

be easier to thin without disturbing the plants you plan to leave if

there is a little space between them. You may want to try

mixing radish seeds with the carrot seeds. The carrot seeds are

slow to germinate, and the radishes, which germinate and grow very

quickly, will mark the row until the carrots come up.

A second crop of carrots can be planted

in late summer or early fall in most areas. If a hard freeze

threatens, protect your fall crop with a heavy mulch.

Maintenance: The

first few weeks after sowing, determine the size of your crop.

Carrots can't tolerate a deep planting in a dry bed, so the trick is

to offer them a shallow sowing with even moisture. The

seedlings grow slowly and can't compete with weeds. Hand

weeding is recommended until the carrots are 2 inches tall.

Thin the carrots 3 inches apart, and then mulch with clean straw

and compost to keep the weeds at bay.

Mulching also helps the soil retain

moisture and prevents "green shoulder," which is caused by exposing

the crowns of the carrots to the sun, making the roots bitter.

If the tops of your carrot roots start to turn green, pull the soil

up around them. Overwatering your carrots can cause the roots

to crack.

Common Problems: The

insect to watch for is the rust fly. Carrots planted after the

first week of June often escape the first generation of rust flies,

and those harvested before September usually escape the second

generation. Interplanting onions or garlic in the carrot beds

will also ward off the villainous flies.

Compost and wood ashes will also scare

off not only rust flies but carrot weevils, wireworms, and other

carrot pests. Probably the best organic way to get rid of

pests is to soak the bed once a week with a thin mixture of wood

ashes and water using a watering can.

Most carrot pests and diseases are

soil-borne and can be controlled by crop rotation.

Harvesting and Storage:

Most carrots can be harvested in less than three

months. The largest carrots will have the darkest, greenest

tops, but don't leave the roots in the ground too long or they will

be tough. Most are at their prime when about an inch in

diameter at the crown.

When harvesting, drench the bed with

water first, making the carrots easier to pull. When you find

a carrot big enough, grasp the greens at the crown and tug gently

with a twisting motion. If the greens snap off, carefully lift

the roots with a spading fork. Use damaged roots right away

and store unblemished ones.

Thick cored carrots store the

best. There are three ways to store fresh carrots:

1.

Leave them in the ground under a heavy mulch.

2.

Store them in a root cellar or underground barrel.

3.

Keep them in the crisper bin of the refrigerator.

If the temperature seldom drops below

20 degrees F, you can leave carrots in the ground all winter. A

thick mulch will help protect them during hard freezes.

**************************************************

CAULIFLOWER

Harvest cauliflower when the heads are about 6 to 8 inches across. As with broccoli, be sure you cut the head before the buds begin to loosen. The plant can be removed after the head is cut.

Harvest cauliflower when the heads are about 6 to 8 inches across. As with broccoli, be sure you cut the head before the buds begin to loosen. The plant can be removed after the head is cut.

Cauliflower does not like hot weather so set your plants out as early as possible. Heads that mature in hot weather will have a bitter taste.

Location: Heads will discolor unless the plants are protected from full sun and frost.

Cultivation: Garden beds should be rich in manure and other organic matter. Supplemental feedings will probably be necessary. The white of the head is preserved by *blanching it* or protecting it from sunlight. While the head is still small, tie the large leaves together over the head. These will be replaced as the head grows.

Planting: Sow seeds 1/4 inch deep and 2 inches apart in seed trays or flats. Seedlings take about 6 weeks to appear and are ready for transplanting when they are around 4-6 inches high. Transplant only in cool weather.

Watering: Water well, but avoid watering directly over the head to prevent damage. Head may need some protection during heavy rainfall.

Fertilizing: Work plenty of manure into the soil. Poultry manure is especially good.

Harvesting: Plants mature in 4-5 months. Remove the heads when they are about 8 inches wide by cutting. If left too long, they will discolor and lose their crisp firmness. Leaves can also be used as a vegetable.

*Blanching Cauliflower*

Blanching cauliflower doesn't make it taste any better, but the snow-white curds of a blanched head are more appetizing than the green, yellow or brown curds you will get from an unblanched head.

The heads are ready to blanch when they are about two inches across. Choose a warm, sunny afternoon to work with your plants, and make sure that they are dry before you begin, because working with wet plants can make them disease and rot. The only supplies you will need are some soft twine or rubber bands.

To blanch the head, pull some of the leaves from the sides of the plant up over the head and secure them with the twine or rubber bands. Cover the head and completely shade it from light and protect it from moisture, but leave openings for air to circulate. Self-blanching cauliflower types such as "Fremont" or "Ravella" have leaves that naturally curl up over the head.

Once you start blanching, never water your plants from the top. Soak the roots, but leave the head and leaves as dry as possible. Unwrap the heads after a hard rain and let them dry out. Check them for insects from time to time. They will grow quickly at this stage, and will probably be ready for harvest in a week or two.

**************************************************

CORN

Corn Growing: Corn

is a warm-weather vegetable that grows best during the long, sunny

days of summer. It needs full sun and windbreaks in areas where

strong winds are a problem. The rule of thumb for seeding corn

is to plant it two weeks before the last expected frost date.

Corn is pollinated by the fall of pollen from male flowers (tassels)

at the top of the stem onto female flowers (silks) lower down.

When corn is pollinating, water at ground level so as not to disturb

the process. To extend your harvest a few weeks, stagger your

corn plantings. This also prevents accidental cross-pollination

of certain varieties. If you plan to plant different varieties

of corn, allow at least 100 feet between them. Otherwise they

will cross pollinate each other, and you will only get one

variety. This is especially important if you will be planting

popcorn, as it usually dominates.

Corn Growing: Corn

is a warm-weather vegetable that grows best during the long, sunny

days of summer. It needs full sun and windbreaks in areas where

strong winds are a problem. The rule of thumb for seeding corn

is to plant it two weeks before the last expected frost date.

Corn is pollinated by the fall of pollen from male flowers (tassels)

at the top of the stem onto female flowers (silks) lower down.

When corn is pollinating, water at ground level so as not to disturb

the process. To extend your harvest a few weeks, stagger your

corn plantings. This also prevents accidental cross-pollination

of certain varieties. If you plan to plant different varieties

of corn, allow at least 100 feet between them. Otherwise they

will cross pollinate each other, and you will only get one

variety. This is especially important if you will be planting

popcorn, as it usually dominates.

Time your plantings by checking the days

to maturity and counting back from the date you want to begin

harvesting. One thing to remember is that the harvest time may

vary slightly if the weather is very cool or very warm during the

growing season. Timing your corn plantings is especially

helpful if you're planning a midsummer vacation away from home.

You needn't miss a single, delicious ear if you plan it right.

Soil and Site: Corn

likes rich soil with good drainage. Ideal soil for corn is

sand that stays moist, without being too wet. The fastest way

to improve less-than-perfect soil is to add plenty of organic matter

(leaves, compost, grass clippings and crop residues). If

possible, work in a 1-inch layer of manure the preceding fall.

Alternatively, you can grow a green manure crop, such as buckwheat,

oats, clover, rye, winter wheat, or vetch that will be plowed under

in the spring. If your soil is too sandy, organic matter will

help it retain nutrients and moisture, which are vital to corn.

If you have heavy clay soil, organic matter will wedge between the

soil's tightly compacted particles to loosen it and improve its

drainage.

As you're planning your garden, whether

on paper or in your head, arrange the corn so it will be in at least

four side-by-side rows to ensure good pollination. Be sure it

gets full sun, away from trees that might shade it. Most corn

varieties are tall and can shade shorter crops, so plant corn on the

north or east side of the garden.

If you've grown corn before in the same

garden, change the place where you plant it, or rotate it, every

year. This can be tricky if you don't have lots of garden

space, but when you rotate corn, you prevent disease and pest

problems from recurring. You also keep your garden's natural

fertility in balance by moving heavy feeders, like corn, around.

If your garden is too small for yearly rotation, rotate it at least

every second or third season. If you run into a bad insect or

disease problem one year, rotation the following season is a must.

Fertilizer -- A Fish Story?

Many gardeners have heard that colonists learned from the

Indians to plant each corn kernel on top of a dead fish. This

is no "fish story". Decaying fish contain nitrogen, which corn

needs for good growth. The Indians and colonists may not have

known why it worked, but they liked the results, so continued to do

it.

Because it needs a steady supply of

nitrogen throughout the growing season, corn is called a "heavy

feeder." It's logical that a plant that can grow over six feet

tall and produce hundreds of seeds needs lots of food. It's not

so much the amount of food that matters as a steady diet while corn

is growing. In fact, at planting time, corn needs about the

same amount of fertilizer as most other garden vegetables.

During the growing season, however, you give corn additional feedings

by side-dressing the crop. Fish emulsion and manure tea are

good choices.

Going along with the notion behind the

dead fish of early American times, you can use an organic fertilizer

such as well-rotted compost, aged or dehydrated animal manures or

concentrated animal or plant extracts like bloodmeal or alfalfa

meal. These materials may be available at little or no cost to

gardeners in some areas. In other areas they may be prepackaged

and sold at garden stores and the prices can be high. An

advantage of these fertilizers is their ability to condition the soil

as well as to feed plants. They also provide nutrients over an

extended period of time, which helps corn.

How to Have the Earliest Corn

If you live in the North, it's not too hard to grow corn

that's "knee high by the Fourth of July," and if you live farther

south you can easily beat that date. Choose an early variety

like 'Earlivee', 'Early Sunglow' or 'Quickie'. Plan to plant

four to six weeks before the last frost date in your area.

Planting Early:

Plant the seed about 1 1/2 to 2 inches deep. If you

want to, you can cover the rows with a plastic tunnel for extra heat

or with chicken wire to protect the seeds from birds.

When the seedlings are 8 to 10 inches

high, give them their first dose of fertilizer. Side-dress

with a balanced fertilizer and then water. Side-dress again

when the plants are knee-high, and give a third nutrient boost when

they tassel. Soon afterward you'll have the first local

corn.

Mulch: Some

gardeners mulch their corn to prevent weeds and to keep the soil

moist. Although mulching can be beneficial in hot, dry

climates, keep in mind that you'll need quite a load of mulch

material - hay, straw, leaves, peat moss, etc. - to take care of a

good stand of corn. As long as you give corn a steady supply

of food and water, it really doesn't require much other care.

Thinning: If you

plant corn in hills or plant the rows too thickly, you'll have to

thin out some plants to make sure the others have enough room to

grow. Thin when the seedlings are about four inches tall.

The best time to thin is after a rain

when the plants have dried but the soil is still moist. The

plants pull easily from the soil without disturbing neighboring

seedlings.

To thin, just pull up enough plants so

that those remaining in the row or hill will be 10 inches

apart. If you crowd your corn a bit - about 8 inches

apart - don't worry, it should do fine; but if you're just getting

the hang of raising corn, give your plants more room.

Planting Methods:

Once the seedbed is well worked and fertilized, you're

ready to plant. There are two traditional ways to plant corn:

three to five seeds grouped together in small circles, or "hills" or

spaced evenly down straight rows, one behind the other.

Weed Control: Weed

your corn every few weeks, starting before you even plant a

seed. Work the soil several times before planting. This

not only conditions the soil, it stirs up and kills tiny weed seeds

lurking near the surface. It also buries some seeds so deeply

that they never get a chance to sprout.

Once the corn is planted, scratch the

surface of the planting bed every week or so with a weeding

rake. When the corn is tall enough to be hilled, you'll

automatically get rid of weeds by covering them with soil as you

hill.

Hilling: Hilling is pulling

up soil to mound it around the base of a plant. When you hill

a young corn plant, the added soil around its stem helps support it

as it grows taller. This protects it from being blown over in

a strong wind. To really anchor plants, it's a good idea to

hill corn every two to three weeks until the plants start to

tassel.

Hilling also covers and smothers any

weeds around the base of your corn plants. You might say

you're creating a "soil mulch" around your plants. If dryness

is a problem, extra soil helps the corn roots retain moisture.

Watering: During a dry

season, watering is essential both when the corn is tasseling and when

the kernels are forming. At this time, the plant is devoting all

its energy to seed production, holding nothing in reserve for a dry

spell. The plants are relatively tall and exposed to the wind and

drying heat of summer, so they often "transpire" or give off moisture

faster than their roots can take it up.

During its growing season, corn needs at

least an inch of water per week. If it has to go through a dry

stretch, it may not produce well. If your garden receives less

than an inch of rain in a week, water.

When you water, water thoroughly.

Try to saturate the ground to a depth of about 4 inches.

Surface dampness will only encourage shallow roots. (Sandy soil

absorbs water faster than clay.) One sign of too little water

is if the corn leaves are curling or rolling. If you want

healthy, sweet, well-filled ears, pay close attention to the weather

at the tail end of the season and water if your corn needs it.

Harvesting: Sweet

corn should be harvested when its ears are completely filled out and

a pierced kernel shows a milky white liquid. You can also tell

by feeling the end of an ear. If it's rounded or blunt rather

than pointed, the ears are ready. The silks also dry up when

the ears are almost ready to be picked. The prime time for

corn to be harvested comes 12-14 weeks after planting and lasts only

a few days, so check repeatedly to see if the corn is ready.

If you are too early, the juice will be

watery. Later, the kernels turn doughy inside as moisture

recedes and sugar turns to starch. Here are some other signs of

readiness:

Dark green

husks.

Brown,

but not brittle, silks.

Well

filled ears.

Sweetness

is the key, so it helps to understand what makes corn sweet and why

timing is so important in your harvest. The plant manufactures

natural sugars when the kernels are filling out. These kernels

are seeds that each contain a natural food-storage compartment as

well as the corn embryo. A seed can't store sugars, but it can

live on stored starches throughout the winter months and in its

early stages of growth the following season. As soon as the

kernels are full of sugar, the plant begins to convert it into

starch. For best flavor, harvest the corn before this change

can take place.

The

sweetness of corn depends on the variety, temperature and amount of

sunlight during the day when the ears are forming. The plant

makes the most sugar on cool, sunny days. If the temperature

is too hot, the sugar-making process is slowed. That's why the

long, crisp, sunny days of early fall produce the sweetest corn.

To harvest

sweet corn, grab an ear and twist it down and off the stalk.

POPCORN

Popcorn Pointers: The

only way that growing popcorn differs from growing sweet corn is

at harvest-time, and popcorn is actually easier to harvest because

you don't have to catch it at the peak of sweetness. Leave

popcorn in the garden until the stalks and husks are brown and dry,

then twist and snap each ear from the stalk. Do this before

the frost hits. To prepare popcorn for indoor curing,

carefully strip away the dried husk from each ear. The kernels

will be partially dried or "cured," a necessity for long-term

storage.

Popcorn Pointers: The

only way that growing popcorn differs from growing sweet corn is

at harvest-time, and popcorn is actually easier to harvest because

you don't have to catch it at the peak of sweetness. Leave

popcorn in the garden until the stalks and husks are brown and dry,

then twist and snap each ear from the stalk. Do this before

the frost hits. To prepare popcorn for indoor curing,

carefully strip away the dried husk from each ear. The kernels

will be partially dried or "cured," a necessity for long-term

storage.

Besides drying on the stalks, popcorn

requires another four to six weeks of thorough drying in a warm,

well-ventilated place. Corn can't pop unless there's the right

amount of moisture inside the kernel. When it's heated, the

moisture turns to steam, which causes the kernel to burst.

Place the ears in mesh bags or spread

them out in an area where they'll have warm air circulating around

them. You can also hang mesh bags full of popcorn ears in your

garage for about four weeks. After curing, hang the bags of

corn from the rafters of your root cellar. The corn can keep

for years in the cool, dry, dark conditions there.

After a month of curing, the kernels

can be taken off the ears and stored in airtight jars. Whether

you're removing the kernels before storage or just before popping,

there's no real trick to it. Simply grasp the ear firmly in

both hands and twist until the kernels drop out. Once started,

the kernels drop off with very little pressure. However, beware

of the sharply pointed kernels if you're using your bare hands.

After two or three ears, you may have a few nicks and scratches.

If you want to remove the kernels from a lot of ears, it might be a

good idea to wear gloves.

Popcorn doesn't take much garden space

for a sizable harvest. Each ear is loaded with tiny kernels

come harvest-time, and three or four five-foot-long rows should be

plenty. Many popcorn varieties produce one or two ears per

plant, so you may have enough by growing just five or six plants.

Pop homegrown popcorn just as you would

store-bought. Heat a few tablespoons of oil in a deep pot.

Sprinkle in enough kernels to coat the bottom and cover the pot.

As soon as you hear the first kernel pop, shake the covered pot

vigorously while the rest pop. When the popping stops, remove

the pot from the heat and take off the lid to let the steam

escape. The popcorn is ready. Enjoy it plain, or add your

favorite topping.

**************************************************

GARLIC

The bulbs

you buy in the grocery store will produce a good crop of

garlic. Since the plants will do most of their growing in

cool weather, it's a good idea to plant them in late summer or early

fall and to mulch the plants over in winter.

The bulbs

you buy in the grocery store will produce a good crop of

garlic. Since the plants will do most of their growing in

cool weather, it's a good idea to plant them in late summer or early

fall and to mulch the plants over in winter.

Planting and Maintenance:

Break each bulb into individual cloves, and plant the

cloves 3 to 4 inches apart, with the pointed end up. Give them

two or three sidedressings with manure or fertilizer during the

season. The soil around them should be kept loose and moist.

Harvesting: Pull up

the bulbs when the tops fall over and die. Let them dry in the

sun for a few days, then braid the tops together or place them in a

net bag. Hanging them in an airy location will help prevent

rot. Peeled garlic cloves may be stored in a jar of oil.

The garlic retains it's flavor and the oil will add flavor to salad

dressings.

Insects and Disease:

Insects:

Thripes are tiny insects that

feed on leaves that cause white, blotchy areas. The plants

weaken and the yield is reduced. Keep weeds out of the garden

to eliminate insect pests. A blast of cold water will remove

thripes from plants. Soap sprays may be also be effective.

Onion Maggots are the offspring of

a small fly that lays eggs near the base of the plant or on the bulb

itself. The maggots kill the plant by burrowing into the stem

and bulb. Pull up and destroy any plants before the maggots

mature into flies.

Disease:

Neck Rot is the most common

problem. It strikes just after harvest or while the bulbs are

in storage. Drying the bulbs at warm temperatures with good

ventilation and storing in a cool, airy spot will help prevent the

disease.

Garlic as a Companion Plant:

Garlic helps deter Japanese beetles, and it makes a great

companion for roses and raspberries.

Medicinal Uses:

Garlic has been used throughout the ages to ward off disease, and

has saved many lives in epidemics of infectious diseases. It

is antibacterial and gives protection against colds and the

flu. Garlic improves circulation and lowers blood

pressure. It was proven in controlled clinical studies to

reduce cholesterol levels. Further studies indicate that garlic

may have a positive role in the prevention of coronary heart disease,

thrombosis and arteriosclerosis. It may even offer some degree

of protection against cancer.

**************************************************

Leaf Crop ABC's

LETTUCE, SPINACH & GREENS

Most

greens crops thrive in cool spring and fall weather (50*F to

60*F). Just compare the crisp, flavorful lettuce leaves

harvested in spring with the often bitter leaves of a summer cutting

and you'll agree. A few greens can handle summer heat, but most

of them prefer the cooler temperatures of spring and fall.

Most

greens crops thrive in cool spring and fall weather (50*F to

60*F). Just compare the crisp, flavorful lettuce leaves

harvested in spring with the often bitter leaves of a summer cutting

and you'll agree. A few greens can handle summer heat, but most

of them prefer the cooler temperatures of spring and fall.

A steady

flow of moisture and nutrients is important for good greens.

Leafy crops need plenty of nitrogen,

too. That's the key element in the good growth of leaves and it

influences the crispness and quality of leafy crops, as well.

The one thing most greens can't take is

a lot of heat. Spinach, for example, will quickly develop a

seedstalk and start to stretch upward when it gets too

warm. This is known as going to seed. When that happens,

spinach leaves begin to lose some of their flavor. A long hot

spell can spoil heads of iceberg-type lettuce, too. The heat

loosens the leaves of the head, and they get soft and sometimes

bitter. If you can shade some of these crops as hot weather

approaches, you can often keep the harvest going a few weeks

longer.

LETTUCE

Some

people may think lettuce is lettuce. Not so! There's a

wonderful assortment. Each has a distinct flavor, texture and

color, so you can have remarkably different salads just by varying

the lettuces you use. Here's a rundown of what you can expect

in the lettuce department:

Head Lettuce: Head,

or crisphead lettuces produce heads of tightly wrapped crisp

leaves. 'Great Lakes', 'Iceberg' and 'Ithaca' are good choices

for home gardeners. Those in the South may want to try

varieties better adapted to hot weather, such as 'Summertime' and

'Continuity'. 'Tom Thumb' is a good miniature iceberg type,

growing only to the size of a tennis ball.

Butterhead or loosehead plants form a

head, but the leaves don't wrap themselves tightly

together. 'Buttercrunch' is a good variety for home

gardeners. Its taste and crispness are terrific. The

leaves are crunchier than leaf lettuce. The outer leaves of the

head are dark green, and the inner leaves are

lighter-colored. 'Dark Green Boston' and 'Bibb' are two other

tasty and popular loosehead varieties. You can harvest some

loosehead plants before they form heads for an early harvest of

delicious leaves. A second crop will follow. To harvest,

simply take a knife and cut the entire plant off about one inch above

the ground.

Leaf Lettuce: Leaf

lettuce doesn't form a head at all - it grows up and out. It's

very easy to plant and will grow anywhere, almost anytime. Make

regular plantings every few weeks over the entire season, starting as

soon as you can work the soil in the spring. That way you

always have lettuce that is young and fresh. Harvest at the

peak of freshness and taste. Harvest leaf lettuces by picking

off the large outer leaves or cutting the plant off an inch above the

ground and letting it grow back. 'Black-Seeded Simpson' is an

old favorite, and one of the earliest leaf lettuces you can

grow. 'Simpson Elite' is a new improved version. 'Oak

Leaf' has thin, tender leaves and takes heat well; 'Red Salad

Bowl' is a red-tinged oakleaf. 'Green Ice' has crinkly leaves

and is one of the slowest to go to seed. Be sure to include

some 'Red Sails' or 'Four Seasons' lettuce, too. They add great

color and taste to a salad, and look beautiful in the garden.

Romaine Lettuce:

Plant seeds very early like other varieties, but plant them

a little thicker because Romaine lettuce doesn't germinate as well as

other kinds of lettuce. The plants produce a tall head - 10

inches or more - of dark green leaves that close up firmly. The

tight, inner leaves are very tasty in tossed salads because they

often have a pleasant, mild taste. Romaine lettuce takes 70 to

80 days to form a full-grown head. You can harvest it earlier,

of course, just like loosehead lettuce. Cut it before it forms

a head, and it will come back to give you an additional

harvest. 'Paris Island' cos is a vigorous, disease-resistant

variety with dark green leaves; 'Rosalita' is a dark red-leafed

cos with good heat tolerance. 'Rouge d'Hiver' is an

early-maturing European red heirloom. 'Winter Density' will

withstand a light frost.

Planning Your Greens Garden

When you

think about greens to grow you've got a big group of plants

to consider, as well as different varieties of some salad

crops.

Planning Tips:

* Plant some lettuce or spinach between your corn rows, or on the

shady side of a row of tomatoes.

* Try multi-planting. Plant

lettuce, carrots and onions in the same wide row (15 to 16 inches

across). Harvest the lettuce when young, leaving expansion

room for carrots and onions. You can mix and match with other

crops, too, including beets and spinach.

Mulching: A thick,

organic mulch (straw, leaves, grass clippings, hay, etc.) is a must

if you're growing head lettuce down South in the spring. It

will help retain moisture and keep the soil cool as warm spring

weather arrives. It's good in Northern gardens, too, where

spring heat or quick-draining soils could hurt the crop.

Cultivation: Be sure

not to kill or hoe around your head lettuce plants deeper than one

inch - their roots are shallow.

Booster Shot of Fertilizer:

Lettuce has a limited root system that can't go deep in the

soil for nutrients. Sometimes an application of extra

fertilizer along the way - known as sidedressing - can

help. Make a light application of fertilizer every three to

four weeks.

Spinach

Spinach

must have at least 6 weeks of cool weather from seeding to

harvest. Plant seeds outdoors 4 to 6 weeks before your last

spring frost date, and again 4 to 6 weeks before the first fall frost

date.

Preparation: Mix

compost, manure, and/or fertilizer into each row or plot before

planting.

Planting: Sow seeds

1/2 inch deep, about 12 seeds per foot of row, or sprinkle them over

a wide row or bed.

Care: When seedlings

are 1 inch tall, thin to stand 4 inches apart. Water every few

days during dry spells; mulch spinach planted in rows to retain soil

moisture.

Harvesting: To

harvest early, cut individual leaves as soon as they are big enough

to eat. When the weather warms up, cut the whole plant close to

the ground, below the lowest leaf. Harvest again after a few

new leaves reappear. Repeat as long as possible.

Sprinkle

in a few radish seeds. After you've broadcast the main

crop, sprinkle some radish seeds down the row. They'll come up

quickly and mark the row. Use about five percent as much radish

seed as the main seed. You can either pull up the radishes

while they're small or harvest them after you pick your crop of

greens.

Watering Greens Crops:

You can't beat greens that are crisp and

succulent. One of the most important things for highest-quality

greens is a steady supply of moisture.

Greens thrive in moist, but not wet,

soil. They require about an inch of rain or irrigation water

per week, and perhaps a little more for summer greens in hot

weather.

If the water supply drops, greens will

probably be the first crops in the garden to show signs of

drought. That's because many of them - especially

lettuce - have limited root systems; and because their large green

leaves give off quite a lot of moisture. Sometimes on a hot,

sunny afternoon many garden plants appear wilted. That's

normal; usually they'll recover by next morning. If they don't,

it's time to water.

Watering Tips:

* Irrigate early in the day to cut down

on evaporation losses and to make your water go further. This

also gives the plants plenty of time to dry out during the

day. (Wet foliage overnight allows disease organisms to spread

rapidly among plants.)

* Soak the soil thoroughly enough that

you don't have to come back and water again the following

day. Try to moisten the soil to a depth of five or six inches,

at least.

* If the soil is dry at planting time,

water as gently as you can after planting, so you don't wash out any

seeds. Be sure to keep the seedbed moist until the plants come

up.

**************************************************

ONIONS

Onions

should be planted well before the last spring frost date.

During the first phase of growth, the onion will be producing lush

green tops. At some point, the tops will quit growing, and the

bulbs will begin to mature.

Onions

should be planted well before the last spring frost date.

During the first phase of growth, the onion will be producing lush

green tops. At some point, the tops will quit growing, and the

bulbs will begin to mature.

Onion

seeds will take 100 to 120 days to mature. Sets, which are

small bulbs started the previous year, will mature three or more

weeks earlier. Onion plants, which are usually purchased in

bundles, will mature at about the same time as the sets. You

will find the widest range of varieties in seeds.

Preparing the Soil:

Onions prefer a well worked soil. The fall before

you plant, dig in compost or manure at the rate of about 20 pounds

per square yard.

In order to give the onions a long

period of growth, seeds can be planted in late August in areas where

winters are not too severe. In colder areas, seeds can be

started indoors. If your season is long enough to give 100 to

120 days for the onions to grow and mature, you can sow seeds

outdoors a month before the final spring frost.

Allow 1/2 ounce of seed for every 100

feet of row to be sown. Place two seeds per inch and cover with

1/4 to 1 inch of soil. Thin once when the seedlings are still

very small and can be transplanted into another row, then again when

they are large enough to be used as green onions. Mature plants

should be three to four inches apart.

Plant Maintenance:

Keep the plants free from weeds, as onions are less

tolerant of crowding than most other vegetables.

Water regularly until the tops start to

yellow, then withhold water and pull the soil back so that the top

two thirds of the bulb shows.

Cultivation should be very shallow,

because the roots are close to the surface.

Harvesting: When the

tops are quite dry, pull the bulbs and let them dry in the sun until

all the dirt on them is dry. Onions can now be prepared for

storage. The long tops can be braided together so that the

onions can be hung in bunches, or they can be hung in net bags or

old stockings. Continue the curing process for several weeks by

keeping them hung in an area where air can circulate freely.

Afterwards, move them into a cool, dry, and preferably dark area for

storage. Use thick necked onions first, since they will not

keep well.

Bunching Onions:

Bunching onions will not form a bulb, but they make the

tastiest green onions. They are a perennial, and should be

planted where you will not run a tiller or cultivator.

Bunching onions are usually planted from

seed, and you can begin harvesting when they are about pencil

size. They will not require mulch and will keep you in onions

year round. When your plants begin to produce flowers, leave

them alone. They will soon reseed themselves.

Onion Problems:

Insects:

Thripes are tiny insects that

feed on leaves that cause white, blotchy areas. The plants

weaken and the yield is reduced. Keep weeds out of the garden

to eliminate insect pests. A blast of cold water will remove

thripes from plants. Soap sprays may be also be effective.

Onion Maggots are the offspring of

a small fly that lays eggs near the base of the plant or on the bulb

itself. The maggots kill the plant by burrowing into the stem

and bulb. Pull up and destroy any plants before the maggots

mature into flies.

Disease:

Neck Rot is the most common

problem. It strikes just after harvest or while the bulbs are

in storage. Drying the bulbs at warm temperatures with good

ventilation and storing in a cool, airy spot will help prevent the

disease.

**************************************************

PEAS

Planting: Peas

should be planted in early spring, well before the last frost.

For an extended harvest, plant early, midseason, and late

varieties. Successive plantings of the same varieties tend to

catch up with each other, resulting in one big harvest.

Planting: Peas

should be planted in early spring, well before the last frost.

For an extended harvest, plant early, midseason, and late

varieties. Successive plantings of the same varieties tend to

catch up with each other, resulting in one big harvest.

It's a good idea to add "inoculant" to

soil or seeds before they are sown. This black powder is

available anywhere seeds are sold. It is not a chemical

additive but a naturally occurring bacterial powder that aids peas'

natural ability to "fix" nitrogen in the soil by forming "peanuts" of

nitrogen on their roots. In addition to helping plants actually

enrich the soil in your garden as they grow and thrive, this

inoculant also boosts the health of vines and the yield.

Climate: Peas like

cool weather, but early plantings of dwarf varieties such as Little

Marvel, Progress No. 9 or Wando will do well in warm climates.

Plant in wide rows so the peas will shade the ground and each

other.

Maintenance: If you

have planted your peas in wide rows, they will shade out any weeds

that may try to come up. They will also help support each

other, so that with dwarf varieties, no other support will be

needed. In Southern gardens, wide rows will also help keep the

soil cool and moist.

Peas are

legumes, and don't need much fertilizer, especially nitrogen.

Good soil that has been enriched with compost is all they need.

Peas need

adequate but not excessive water at soil level. Avoid watering

over the tops of mature leaves and flowers.

Harvesting: Pick

when the pods are full, firm, shining and bright green in color.

The sugar content will be high at this time. Frequent

harvesting from the bottom of the plant prolongs the harvest.

Be careful when pulling the pods so that the vine is not damaged.

Crop Rotation: Crop

rotation is a preventative measure which will stop the growth of

diseases affecting the plant. After harvesting, remove all

vines and burn them. They usually contain a variety of

diseases and are not suitable for composting. Plant peas in a

different section of the garden next year.

Companions: Good

companions for peas include bush beans, pole beans, carrots, corn,

cucumber, radish and turnips. Don't plant near onions.

**************************************************

PEPPERS

Peppers

are fast becoming one of the most popular of all vegetables to grow,

second only to tomatoes. There are hundreds of varieties

available especially if you grow them from seed. They come in

all shapes and colors, and range from the sweetest to downright

fiery.

Peppers

are fast becoming one of the most popular of all vegetables to grow,

second only to tomatoes. There are hundreds of varieties

available especially if you grow them from seed. They come in

all shapes and colors, and range from the sweetest to downright

fiery.

Often,

gardeners get addicted to growing peppers by chance. They buy a

variety at the local nursery for fun and to experiment. It

turned out to be such a success, that the next year they plant

three.

There are

almost as many varieties as there are of tomatoes! They come

in various shapes and sizes from small tapered or ball shaped ones to

long cones and big round bells. Thick fleshed ones are best for

roasting and cooking, while the thinner ones are great for eating

raw. And some of them are HOT!

Seeds and Seedlings:

Only the most common types - banana and bell types are

usually available as started seedlings for transplanting into the

garden. For small gardens, these are the best way to go.

Peppers cannot be planted out until the

outdoor soil and night temperatures remain above 65

degrees. Planting out too early in cold and wet conditions will

stunt them and harm fruit production. But remember, they must

be hardened off just like your tomatoes before planting out.

Pepper Pointers:

Peppers, especially hot pepper plants with their usually

small and colorful fruits, are ideal for spot planting around a

garden. When growing peppers in beds, avoid planting the

peppers where other members of the nightshade family have been

previously planted as they are subject to similar diseases. To

prevent cross-pollination, hot pepper plants should not be planted

near sweet or bell pepper plants.

When buying pepper plants choose those

that are sturdy with deep green leaves and without fruit or

blossoms.

Choose a location in your garden, patio

or home that receives morning sun - and at least 6 hours of sun

daily.

While full sun and heat are good for

peppers, too much can damage the fruit. Protect them from

intense afternoon sun with taller plants (or beans on a trellis), by

planting them in a block no more than 1½ feet apart.

Transplant pepper plants to garden beds

two to three weeks after the last frost and when the soil temperature

is at least 65 °F (18 °C).

When transferring pepper plants to a

garden bed or container, do it in the evening or on a cloudy day to

reduce the chance of sunscald.

Keep the soil moist, not soggy, to

encourage root development and prevent blossom wilting and

bitter-tasting peppers. Use a mulch, such as straw, grass

clippings or plastic mulch, to keep moisture in and protect roots.

Ensure that the soil drains well, so

that the roots aren't sitting in water. Raised beds are helpful

in poor-draining garden soil.

Soil Preparation:

Peppers enjoy soil that contains plenty of organic matter,

supplemented with a balanced fertilizer or better yet, one with

slightly higher nitrogen and phosphorous levels. Place in an

area that will receive the most sun and plant 18 inches apart with

rows 3 feet apart. Soil must be well drained. Work the

top 8-10 inches of soil several weeks before planting. Break up

any large clods. Remove rocks, weeds, etc.

If possible, spread 2-3 inches of

organic material over the planting area. You can use materials

such as compost, leaves, peat moss or rotted hay. Work it into

the top 4-6 inches of soil. Work the garden soil only when it

is dry enough not to stick to the garden tools. This is

particularly important if you have clay soil.

Planting: Two to 3

weeks after your last frost, plant out your healthy, green plants

6-8 inches tall. Make the transplant holes at least 3-4 inches

deep so they will grow roots from the stem and better feed the

plant. Small fruiting varieties can go in at 1-1.5 feet

apart. Bell pepper plants will require more space, and may

require staking or caging to support the heavy fruit, so get those in

place at planting time. Choose a cloudy day or an evening to

plant.

Watering: Water the

plants slowly and deeply to help grow a strong root system. Do

not let them wilt, or yields and fruit quality will be

low. Prolonged hot days may require that you create some

temporary shade for them during the hottest part of the

day. Use anything from sheets of cardboard or wood, or erecting

a frame to hold an opaque blanket, etc. that will shade the

plants.

Keep the watering regular to avoid

alternating wet and drought. Fluctuating moisture levels will

cause wilt and blossom end rot.

Harvesting: Pick

peppers at either their immature green stage, or when they reach

their fully ripe red, orange or even brown stages. Use garden

shears to cut them from the stem, as pulling them will result in

breaking off the stem. Cool them as soon as possible after

harvesting to retain flavor and quality. If you have to rush

out to pick green ones on the eve of a frost warning, treat them like

tomatoes to get a bit more ripening. Store them in layers

between sheets of newspaper in a good, sturdy brown paper

bag. Close the top of the bag and store in a slightly cool, but

dark place to allow them to ripen properly. They will shrivel

during this process.

Storing: Peppers can

be stored in the refrigerator for several weeks, but they will lose

their peak flavor after a few days, so eat them fresh or cook them up

as soon as possible.

**************************************************

RADISH

Radishes

are one of the easiest vegetables for the home gardener to cultivate,

and they can be grown in all climates. They grow quickly and

become hot and bitter if left in the ground too long. The small

globe varieties are eaten fresh in salads and used as garnishes,

while the long root forms are used for cooking.

Radishes

are one of the easiest vegetables for the home gardener to cultivate,

and they can be grown in all climates. They grow quickly and

become hot and bitter if left in the ground too long. The small

globe varieties are eaten fresh in salads and used as garnishes,

while the long root forms are used for cooking.

Radishes

are grown throughout the year, and there are many varieties that do

well in cool weather. Sow radishes successively every two to

three weeks for a continuous crop. Radishes can be sown with

slower growing vegetables since they will mature quickly and can be

harvested long before other vegetables will need the space.

Radishes can be planted in lightly shaded places where other

vegetables would be reluctant to thrive.

Plant

seeds directly where they are to grow about 1/4 inch deep and 2

inches apart. Seedlings will appear in 1 to 2 weeks. Keep

the soil moist during the growing period. It's a good idea to

feed seedlings weekly with a complete liquid fertilizer.

Radishes

are ready to harvest 4 to 5 weeks after planting. Plants left

in the ground too long will be inedible.

**************************************************

RHUBARB

This is a very old copy of a newspaper article that the Traverse City Record Eagle ran about a rhubarb plant I grew. In this picture, my daughter Tammy was 3 years old. The rhubarb leaf was 3'X3'.

This is a very old copy of a newspaper article that the Traverse City Record Eagle ran about a rhubarb plant I grew. In this picture, my daughter Tammy was 3 years old. The rhubarb leaf was 3'X3'.

Rhubarb

is a vegetable with a unique taste that makes it a favorite in pies

and desserts. Rhubarb is often mistaken to be a fruit but

rhubarb is actually a member of the vegetable family. Rhubarb

is rich in vitamin C.

Rhubarb

is a vegetable with a unique taste that makes it a favorite in pies

and desserts. Rhubarb is often mistaken to be a fruit but

rhubarb is actually a member of the vegetable family. Rhubarb

is rich in vitamin C.

Rhubarb is

a perennial plant.

Rhubarb

leaves grow from the ground in early spring. The leaves can

grow up to a foot or more in width and length and the plant may grow

to a height of several feet. The blade or green leaves of the

plant are poisonous. They contain high concentrations of oxalic

acid crystals which can cause serious problems when eaten.

These crystals can cause the tongue and throat to swell, preventing

breathing. The edible stalks are up to 18 inches long, 1 to 2

inches in diameter, and generally somewhat hemispherical in cross

section. These stalks are cut and used in pies, jams, jellies,

sauces and juice.

Once

planted, rhubarb plantings remain productive for 8 to 15

years.

Rhubarb

tolerates most soils but grows best in fertile, well-drained soils

that are high in organic matter.

Rhubarb is

relatively free of insect and disease problems.

Rhubarb

responds well to fertilizers. The quality of the crop harvested

depends to a large extent on the care and fertilization

received. Fertilize each year and cultivate shallowly as often

as necessary to remove weeds.

Plant

rhubarb roots in early spring. Plant the roots with the crown

bud 2 inches below the surface of the soil. The hole for the

crown should be dug extra large and composted manure, peat moss or

dairy organic should be mixed with the soil to be placed around the

roots. Firm the soil around the roots but keep it loose over

the buds. Water the crowns after planting.

Good

garden drainage is essential in growing rhubarb. For home

gardeners, planting in raised beds helps ensure against rotting of

the crowns.

Rhubarb

responds to good care and watering. Remove the flower stalks

as they are seen. During the first year of planting, the stalks

should not be picked, since food from the leaves is needed to nourish

the roots for the next year's growth. One light picking may be

taken during the year following planting if the plants are vigorous,

and beginning the second year following planting, the entire plant

may be harvested. When harvesting rhubarb, the first step is

to cut the stalks at the soil line or simply pull them out

individually. All of the stalks of a plant may be harvested

at one time, or pulled out selectively over a 4-6 week period.

After the stalks are cut, the leaves may be removed. If the

stems appear soft and mushy, do not eat them.